Nigeria’s Financial Inclusion Journey

In a decade and a half, Nigeria has made undeniable progress. Formal financial access rose from 26% in 2008 to 64% in 2023, supported by three successive strategies:

The first strategy document (NFIS 1.0, 2012–2018) sought to achieve a financial inclusion rate of 80% (by 2020), up from a baseline of 46.3% in 2010. Its main focus was on laying the foundation by setting targets, creating an enabling environment and building the infrastructure to expand access.

The revised strategy (NFIS 2.0, c. 2018) was a recalibration of the financial inclusion goals, marked by a reduction of the target inclusion rate to 70% of adults formally included by 2020. It represented a mid-course correction, following an assessment of progress, and a doubling down on digital finance and agent networks as key delivery channels.

The most recent strategy update (NFIS 3.0, 2022) set ambitious targets, seeking to cut financial exclusion to 5% by 2024. It emphasised a multi-pronged approach, including a national FinTech strategy, women-focused agent expansion, the rollout of the e-Naira, and payment system innovation captured in the Payment System Vision 2025.

These strategies have driven undeniable progress. Account ownership more than doubled between 2011 and 2023, agent networks expanded rapidly, and digital payments are now part of the daily life of millions of Nigerians. By traditional measures of access and usage, Nigeria has been one of the fastest-moving markets globally.

But beneath the progress lies a paradox.

The Access–Health Paradox

EFInA’s 2023 Access to Financial Services survey found that while 64% of adults are formally included, only 16% are financially healthy. Most households, though “included,” cannot reliably meet basic needs, recover from shocks, or plan ahead. Four in five adults ran out of money in 2023. Nearly three in five went without food or medicine. In addition, 78% could not raise ₦75,000 in an emergency.

The reality is stark: access is rising, but resilience is declining.

What is Financial Health?

Financial health goes beyond accounts and payments. It measures whether people can:

- Meet daily expenses reliably, without constant shortfall (Spending)

- Maintain buffers to cover future needs and unexpected demands (Saving)

- Set long-term goals and actively work towards them (Planning)

- Manage shocks in ways that sustain resilience and enable opportunity, without collapse (Managing Risks)

Together, these four pillars demonstrate how access can translate into outcomes. They shift the question from “Do Nigerians have accounts?” to “Can Nigerians use finance to live better, safer, and more secure lives?”

Nigeria’s Financial Health Crisis

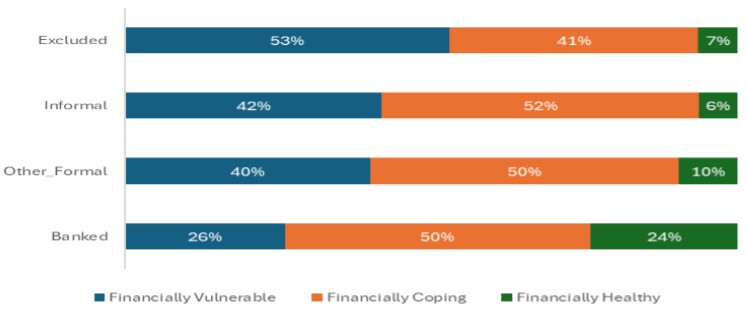

Access Strand by Financial Health Indicators (2023)

Across all “access strands”, most individuals are either coping financially or vulnerable – signs of low financial health. It is, however, important to highlight that the highest rate of financial vulnerability was measured among the group of adults “Excluded” from the formal financial system. In contrast, being “Banked” appears strongly correlated with improved financial health, as this group has the highest percentage of individuals, albeit at only 24%.

Perhaps most worrying; nearly half of adult Nigerians are now “financially coping.” This fragile majority is just getting by, not yet vulnerable, but one shock away from sliding backwards. Inflation, job losses, or policy changes could quickly tip millions into deeper distress.

The story of declining resilience is similar across population segments, with the sharpest declines among women (25% to 12% financially healthy) and youths (15-29 years) (23% to just 11% financially healthy), exposing the groups most critical to Nigeria’s future to deepening vulnerability. In short, while access to financial services has expanded, the financial health of Nigerians is deteriorating, exposing a crisis that demands urgent policy reorientation.

Why Access Alone Falls Short

The system has built the pipes but not the lifelines.

- Payments without resilience: Past strategies rightly prioritised expanding accounts and payment rails, but these were not accompanied by resilience-building tools. Accounts are used mainly for transactions, not for savings, insurance, or credit that buffer shocks. Formal credit stands at 9%, while insurance uptake is just 3% (Findex, 2025), evidence that the architecture of access has not translated into real safety nets. If Nigeria’s inclusion agenda continues to measure success by account numbers alone, we risk building an impressive financial system that fails to improve lives.

- Mismatch of products and needs: Financial tools rarely solve real risks, like sudden health shocks, farming losses, or working capital needs for small businesses to match cash flow volatility. Instead, the market has leaned towards digital loans, while commitment savings, micro-insurance, and crop-linked credit remain scarce. This reflects a policy design gap: the new NFIS should incentivise uptake and innovation aligned with people’s real vulnerabilities.

- Low financial capability: Many Nigerians lack the knowledge or confidence to use financial tools effectively. The 2023 A2F survey shows that across critical dimensions such as budget control, planning, financial choice, and knowledge, Nigerians exhibit consistently low financial capability, with a large share of adults in the “low” and “medium” categories. Many do not understand how to invest, have never heard of securities, or find investing too complicated. For insurance, many do not know its benefits, do not know where to get it, or have simply never thought about it, highlighting both low awareness and weak financial planning. In relation to credit, 3 in 10 adults say they “prefer to live within their means,” despite widespread financial distress, showing limited understanding of credit as a tool for resilience. These patterns illustrate how low financial capability, manifesting as misinformation, low awareness, and weak financial planning, prevents Nigerians from adopting solutions that could protect them from shocks and build long-term financial stability.

- Deep divides: Women, youth, rural and northern populations remain the most excluded from both access and resilience perspectives. The Northern, rural, and female population are more likely to have less income and less education, traits that make them not only less likely to be financially included but also less likely to optimise the gains of inclusion. They are also less likely to own smartphones and are often excluded from digital KYC processes. Youths, though more digitally engaged, experience the greatest difficulty accessing emergency funds.

Why NFIS 4.0 Must Put Financial Health First

As Nigeria prepares its next strategy, the central question must shift from how many are included to how resilient those included are.

A financial health–focused NFIS would:

- Align better with national priorities, from poverty reduction to health insurance and youth empowerment.

- Strengthen flagship government programmes such as Conditional Cash Transfers, NELFUND student loans, and NHIA enrolment by ensuring they improve household well-being, not just enrolment figures.

- Provide guardrails for growth, ensuring pensions, credit, and capital market expansion do not worsen indebtedness or fragility.

- Position Nigeria for the future, equipping households to withstand climate shocks, inflation, and global volatility.

The Global Shift

Globally, inclusion agendas are moving beyond access to outcomes. The US, UNCDF, and Kenya are integrating financial health as a policy compass, recognising that payments alone do not secure resilience. Nigeria risks lagging if NFIS 4.0 does not make this pivot.

A Call to Action

NFIS 4.0 must:

- Measure outcomes, not just access: Track resilience, food and health security, and the ability to raise emergency funds. The current NFIS has driven progress in access and usage, but aligning closely with financial health would ensure the strategy directly contributes to the nation’s socio-economic objectives. Without this shift, inclusion remains an illusion; a metric of access without evidence of real impact.

- Balance the policy mix: Elevate savings, credit, insurance, pensions, and investments alongside payments to ensure a more balanced financial system, one that promotes financial resilience.

- Design for household realities: These are irregular incomes, low trust, and high vulnerability. Past strategies assumed that access naturally leads to usage, and usage to impact. The data disproves this. Nigerians’ financial lives are shaped by irregular incomes, high vulnerability to shocks, and low trust in institutions. The next NFIS must design delivery mechanisms around these realities, support products that align with cash-flow cycles, bundle financial products like insurance and pension with social programs, and strengthen consumer protection and literacy.

- Broaden collaboration across ministries, regulators, providers, and civil society. Building financial health requires more than setting targets or expanding agent networks. It demands coordination across government ministries (e.g. health, agriculture, humanitarian affairs and finance), financial service providers, donors, and civil society to ensure financial tools are relevant, trusted, and widely adopted. The NFIS must seek to formalise these cross-sectoral linkages.

- Evolve data systems: The A2F survey has been invaluable in measuring inclusion trends. Going forward, Nigeria must institutionalise the regular collection of financial health metrics: stress levels, resilience markers, and demographic disparities, to guide adaptive policymaking. Without such feedback loops, the NFIS risks perpetuating the access–impact gap

Conclusion

Nigeria has achieved much in expanding access. But access without resilience is an illusion. If families still go hungry, if one illness wipes out savings, or if the future feels impossible to plan for, then inclusion has failed its purpose.

As Nigeria prepares for NFIS 4.0 and A2F 2025, the choice is clear: celebrate account numbers or measure real improvements in people’s lives and livelihoods after embedding financial health indicators in policy, strengthening consumer trust and protection, designing relevant and affordable products, and addressing deep gender and geographic divides.

If we fail to act now, we risk widening inequalities and entrenching fragility. True financial inclusion is not just about access; it is about resilience, opportunity, and shared prosperity.